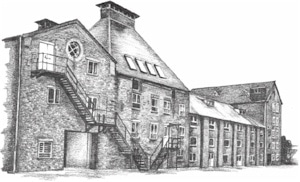

A visit to French and Jupps in Hertfordshire.

For years, London brewers bought much of their Malt from North-East Hertfordshire, where the main centres of trade were at Baldock (on the Great North Road) and Ware (on Ermine Street). The latter’s importance was enhanced by its position on the River Lea, Which winds 42 Miles from its source at Leagrave (Bedfordshire) to the river Thames at Bow Creek.

By Ian Hornsey

“and malt does more than Milton can, To justify God’s way to man, Ale man, ale’s the stuff to drink, For fellows whom it hurts to think.”

A.E Houseman- A Shropshire Lad

In addition to the seaways, the rivers Thames and Lea have historically provided two main routes through which barley and malt flowed into London. Although larger, The Thames played the more modest role, for the Lea tapped into some of the best barley county in Britain, with the region centring on Ware, Hoddesdon, and Stanstead Abbots becoming sophisticated and innovative malting centres. Their position was reinforced when the Lea Navigation was completed in 1739.

French & Jupp’s is a family business, which has been run by the Jupp family from its inception in 1867. David, the present Managing Director, is the fifth generation to do so. The Jupp connection with the Malting, however, goes back much further than that to at least the late 17th century when members of the Jupp family were engaged in farming and malting on, and around, the South Downs in West Sussex. Much of their produce ended up at Dell Quay, the port for Chichester, where it was traded all over the world, whilst some of their malt was taken by barge around the south coast, and up the Thames to supply certain London Brewers.

During the 18th century, a trading relationship developed with William Whitbread’s brewing, distilling and rectifying business in Old Brentford, and this led Jupp’s to acquire a malting in the Middlesex town to supply their needs. By 1780, one William Jupp occupied a single malthouse there, by 1826 Wm. Jupp & son were listed as ‘Coal and Corn merchants’. In 1847, an extensive malthouse was leased at Strand on the Green, by the Thames at Kew Bridge, and Jupps Wharf, at the end of the Grand Union Canal, was also part of their portfolio. The 1881 census showed the company employing 66 men and boys which led one contemporary local commentator to observe that “Jupps had malting sewn up’ by the end of the 19th Century”.Accounts Journal

(mid-1800’s)

During the mid 19th Century, much malt was being supplied to London mega-brewers, such as Samuel Whitbread and Benjamin Truman, and this was taken up to Tower Bridge by sailing barge. The main carrier was a local farmer Margaret French, and the business relationship was obviously highly successful, for she was taken into partnership in 1867. There was a great demand for Dark malts ( mainly for London porter), and, in the same year, the firm opened a roasting plant in Bell Lane, close by Liverpool Street station.

Unsurprisingly, there were problems with smoke, and, in September of that year, French & Jupps received a notice of proceedings under the ‘Nuisances Removal Acts for England’. Having resolved the ‘nuisance’ problem, the firm prospered during the heyday in the British brewing industry, and 1889 enlarged their Maltings Capacity by purchasing premises from H.A & D. Taylor in Stanstead Abbots. Other sites were subsequently purchased in the Hertfordshire town and the whole enterprise moved there in 1896, with cottages being built for those employees who relocated from London.

Greater efficiency could now be achieved since the company was closer to many of their growers, and the town was now well served by rail links to London. In those far-off days, blackened Malts were major products and to produce them, barley was malted at one end of the town (on the present site), and the lightly- kilned green malt was placed in bags, and taken by horse and cart to a factory at the other end of town (on the present site), and the lightly- kilned green malt was placed in bags, and taken by horse and cart to a factory at the other end of town (by St Margaret’s station; it was purchased in 1896), where it was roasted. This facility was used until 1963 when it was destroyed by fire.

Porter Brewing

Brown Malt, another significant item(mostly destined for the London porter market), was malted and kilned on the present site, using time-honoured methods which were very labour intensive. For this reason, only small batches (10 quarters or around 1.5 tonnes) could be made at a time. Green Malt was introduced (to a depth of around 12cm) onto the deck of a small, natural draught kiln, fired by faggots and poles of hornbeam, (occasionally ash) from nearby Hatfield forest. Hornbeam faggots

The Kiln deck was made of woven wire, and the fire was positioned well below, Kiln temperature was controlled by means of water applications and the developing malt was turned by hand on the kiln floor! Initially, a moderate heat would be applied to partially dry the malt, the fire being dampened down periodically. The fire was then allowed to go out, and, after cooling, the malt was carefully turned, before the fire was then vigorously renewed, and the heat became more intense.

In this heat, the grains became swollen and would burst with a loud ‘snapping’ noise, hence the names ‘blown’ or ‘snapped’ malt. Estimates vary, but the first kilning would have been around 105-120 C for around 90 minutes and the final kiln temperature at around 160-170c for the final 30 minutes. The product was deep brown, with a caramel/bitter flavour and a harsh smokiness. It had virtually no enzymic activity. Old records suggest that such malt would have had an extract of 262-267 1/KG, a colour of around 63 EBC, and moisture close to 1%. Because of the way it was roasted, brown malt production was fraught with danger, and fires were not uncommon. Today’s brown malt, now produced in roasting drums, is not smoky and is not blown. It is cooked at a low temperature so as to impart a dryer, less sweet, character than crystal malt. It has a dry extract in the 265-275 KG range, a colour of 130 EBC, and a moisture of <3.5%.

In the UK, roasting was first permitted as a result of the ‘Roasted Malt Act’ of 1842, which stated that: “malt is not to be roasted for sale, or sold, except by persons duly licensed”. The special licence, or patent, led to the products being referred to as ‘patent malts’. ‘Speciality malts’ was another epithet applied to them, and the manufacture of such products has always required intensive energy usage, capital investment, technology, highly skilled and experienced supervision and quality control. All coloured malts are now produced in roasting cylinders, which are essentially modified coffee roasters. Add the high-dry weight losses incurred in production (3.5 tonnes of green malt produce 2.2 tonnes of the final product); special malts are expensive to make.

Speciality malts

Pale (‘white’) malts were also produced for many years, as was distilling malt, and wheat and oat malts. All of these lines had disappeared from the catalogue by the early 1970s when the company made a conscious decision to concentrate on coloured malt production. The last ‘white steep’ was in 1977. Products in the present French & Jupps portfolio are prepared from three main raw materials: barley (malting quality irrelevant); malt (off the kiln at 4-8 % moisture), and green malt (well modified, but unkilned). Only winter barleys are used, because of their tougher ‘skin’, and bolder, larger grain. Pearl and Cassata are favoured varieties for crystal and most patent malts, whilst both roasted barley and black malt use the popular, two-row, winter feed barley Carat as their raw material.#

Well-dressed, sound barley, with a moisture content of 12-16% is converted to roasted barley (which in the UK is regarded as a ‘special malt’) in direct-fired drums in a process that takes around 2.5 hours. The roasting temperature is raised over the first two hours from 80 C to 180 and then raised to 230C whence the grain is approaching combustibility. Colour develops rapidly and inspection samples must be taken at regular intervals.

The amount of heat applied in the final stages is continually reduced until the temperature reaches about 215C at which point the burners are turned off. If the colour is judged to be correct, the load is quenched with sprays of water (anywhere between 45-200 litres per tonne) As is to be expected, the fire risk is considerable. With a colour of 1200 EBC, roasted barley has a totally different flavour from roasted malts (variously described as sharp, dry, astringent and burnt) and is seemingly an essential constituent ingredient of stouts. There is no enzymic activity, and HWEs are in the range of 260-275 KG.

The highly coloured chocolate and black malts (with no enzymic activity) are made in a similar manner except that they originate from malt, rather than barley. Plump grain, with moderate nitrogen content, is malted and after four days of germination, the green malt is lightly kiln-dried down to 6% moisture. At this moisture level, grain can be stored prior to roasting. Roasting commences at about 75C and temperature is increased over the next half hour to 160-175C, at which point the unpleasant white fumes are released by the malt.

The temperature is now gradually increased to a level dictated by the type of malt being produced. As temperatures rise the fumes emitted become bluish in colour and much acrider. For chocolate, malt temperature is raised to around 215C and for black malt, 220-225C is the finishing temperature. When the operator deems that the colour is correct, the heat is turned off and the malt is sprinkled with water, which instantly turns to steam. At the same time, the malt grains swell. Care should be taken to avoid charring and the husk should appear polished. When sectioned, The endosperm should be friable, not steely, glassy or charred. Black malt has a dry extract of 260-275kg, a normal colour of 1300 EBC (range 1200-1400) and <3.5% moisture. Chocolate malt comes in at a similar dry extract and moisture, and a normal colour of 1000 EBC.

Crystal malt is the most widely used coloured malt in the UK, being an almost universal constituent of a ‘typical ale’ grist. It is primarily used for colour control and for its flavour contribution. Like its less-coloured sister Cara Malt, it is manufactured by means of a stewing process in which mist green malt is held at a temperature that encourages the endosperm to be converted to fermentable sugars (i.E ‘mash itself) which then liquefy. When the grains are cooled and dried, this sugary liquid solidifies and is replaced by a semi-crystalline, glassy mass (not unlike barley sugar). Crystal malt imparts delicious characteristic flavours to a beer, which have been variously described as malty, caramel, toffee-like, biscuit and roasted. Crystal malt also aids head retention and shelf-life capabilities, as well as retarding the development of stale characters.

In past times, green malt (sometimes given a water spray) was loaded onto the kiln in a thick layer, trampled down and covered with tarpaulin to reduce evaporation. The temperature was then increased to 60-70 C and held for anything between half and two hours, during which time the malt endosperms liquefied. The tarpaulin was then removed, the temperature raised and the grain ventilated to dry the malt, caramelise sugars and encourage melanoidin formation. The degree of temperature rise would determine how much colour was induced in the grain, with 120-150C yielding relatively dark products.

Three main types of crystal

French & Jupps produce three main crystal malt specifications (for the UK and US brewing industries and for the food industry). Fully modified green malt (43-45% moisture) is loaded into a roasting cylinder and direct-fired at about 50C for 5-10 minutes to remove surface moisture. The drum is then closed to prevent further evaporation and the temperature increased via external heating to 65-70c, whence saccharification takes place and the endosperm liquefies. Temperature is gradually raised to 100C to complete liquefaction (the operator squeezes the grain, and a clear liquid is extruded). Direct heat is reapplied to develop the desired colour, flavour and aroma. The times and final temperature of the roast depending on the specification required, but usually take 2.25 – 2.5 hours and at a temperature of 130-135 C. Dry extracts are in the 270-285 1/Kg range, moisture from 3-5% and the colour from 75 to 300 EBC. Most UK brewers specify the 120-140 product.

Caramalt is a very low-colour crystal malt, which has an almost glassy endosperm. It has been subjected to lower ‘post-stewing’ temperatures than the darker crystal malts, with concomitant lower levels of caramelisation and melanoidin production. Caramalt provides greater sweetness and a stronger caramel flavour than crystal malt and does no possess the latter’s harsher nutty roasted flavours. It greatly improves body, foam retention and beer stability, but makes a negligible colour contribution- hence its popularity with lager brewers. Extracts range from 265-280 l/KG, moisture is <7.5% and colour from 20-30 EBC.

With the help of tasting panels from BRI, a new, low colour roasted caramel malt has recently been developed for lager brewing. The result, Cara Gold, has colour only slightly higher than that of a normal lager malt, but it produces a fuller, rounder and more caramel-like flavour. The procedure used was to make caramel malt at the lowest practicable temperature, without raising the heat during drying, until a high percentage of moisture had been driven off. Results of the BRI assessment are shown in table 1, and show that malty, fruity and toffee flavour notes are carried through to the beer. The low malt colour (10 EBC_ produces a golden-orange lager with increased body and fullness. Such beers have a softer, rounder mouth-feel and improved drinkability.

All local barley

All barley is supplied by local merchants, who enjoy a close relationship with the growers. There is a daily delivery of barley, which is screened, analysed and placed in storage bins, from where it goes via steeps to germination drums. There are six steeps (3 x 17 tonne), with the contents of one drum representing one day’s malt for roasting (e.g crystal).

In an otherwise contracting industry. French & Jupps have trebled output since 1980 and are now producing to capacity. At one time, trade was all UK brewery-based, but now only one-third of the output follows this route. The remaining sales are evenly split between the food industry and the export market (mainly the US). French & Jupps now have an agency in North America, which means that they are able to provide an efficient service to the burgeoning craft-brewing scene ‘over the pond’.

To facilitate this expansion is output, the company has undertaken three major capital investments over the last five years: purchase of a new kiln; installation of a new SCADA centralised control system for malt movement, and the acquisition of a Barth roasting drum from the, now defunct, Park Royal Brewery. In addition, computerised temperature control and humidification systems have been installed in the germination drums.

Much ancillary work has been completed as well and all of these measures have ensured that a high malt quality level can be maintained; as David Jupp said: ” our family have a long and proud history of producing coloured malt and, by having the confidence o invest substantially in our plant in recent years, we are well-positioned to take advantage of opportunities that will arise in the future.”